Xenomorph to Xenofeminsim

Giger’s proto-special effects frontrun reality & what we can learn about the coming digitalization of culture.

Giger’s proto-special effects frontrun reality & what we can learn about the coming digitalization of culture.

By Jak Ritger - Feb 16, 2022

Creeping through the octagonal corridors of Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon, the bureaucratic backdrop drips with ectoplasm: no doubt the result of a trans-dimensional accident that let loose into the late 20th century’s collective unconscious one of the most terrifying creatures of fiction: H.R. Giger’s Xenomorph. Confronting the Swiss artist’s unspeakable hybrid up close, it becomes clear that the Xenomorph is propelled by an ancient future beyond human awareness, exterior to all logics. Extending its monstrous nested mouths through sequences of pencil sketches, the creature seems to breathe anew. I flee Berlin, but the abysmal creature follows me, taking up fresh residence in Lomex Gallery, New York. But why now? Why has it taken so long for the Xenomorph to skitter through the unmapped ventilation ducts of culture’s past four decades to drop like a biomechanical spider into the midst of the fine art world? And what can this recent emergence tell us about our moment of rapid digitalization?

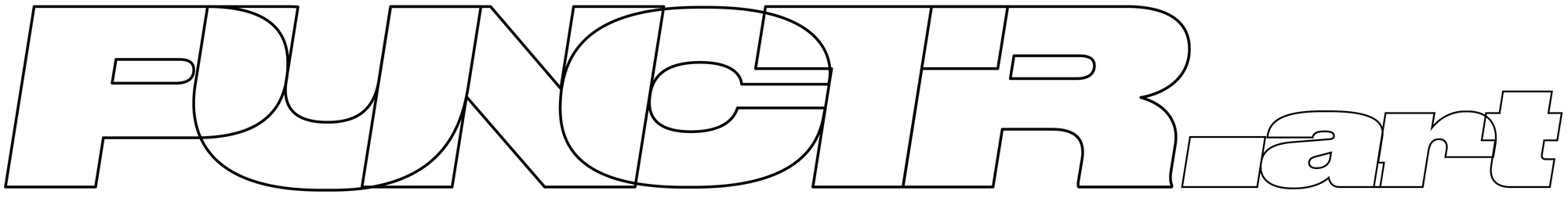

HRGNYC is the largest exhibition of Giger’s work stateside in three decades. The collection presents work from all stages of the artist’s life, from early airbrush sketches to fully realized, elaborate biomechanical sculptures. Giger painted densely twisted bodies woven with wires, tubes, gears and pistons. It is impossible to say where a body begins or an machine ends and all surfaces are an appliqué of technology. Often figures are locked in a violent embrace or are in a state of symbiosis. The sense of light in Giger’s work is uncanny, moonlight reflecting off mineral walls, or a glow emanating from inside the organism. Alongside Giger’s original works is a trove of archival documentation that includes a series of photographs, taken by Chris Stein of Blondie, that documents the production of Giger’s artwork for Debbie Harry’s record KooKoo (1981). In her introduction to a publication of the series, experimental novelist, Stephanie La Cava frames,

“Stein’s photos are essential to Giger’s legacy as an artist, and less so as evidence of celebrity friends. These images secure Giger as the maker of proto-special effects, by showing that they are not special effects at all. These are real objects, props and stylings, not animation, files, or digital ledgers.”

Giger’s baroque dramas compress into single images the coming emotional manipulations of Hollywood Science Fiction we would grow accustom too. Whereas surrealist of the time working in similar modes (George Tooker or Richard Oelze for example) created recognizable allegory or abstract material studies, Giger’s work seems to be antagonistic towards possible incorporation of his graphic narratives. This totalizing fantasy recalls the uneasy wonder of Pixar’s hyper-real animation or the body horror of A.I. generated images: the feeling that our framework for understanding pictures is being eroded. Perhaps it is these qualities that make the music videos for Backfired and Now I Know You Know feel surprisingly current. With the dissonance between the gothic horror visual and smooth trance-y rock, could this is the first instance hyperpop?

One of Giger’s reoccurring themes was the violence of birth. Alien embryos are loaded into the chamber of a gun, next in line to be combusted into being. The biomechanical life of Giger’s world feels both post-human and terribly carnal. This fusion of human and machine can be read as an intensifying, fever-dream response to the mechanized production processes and cybernetic control systems that began to increasingly shape existence over the course of the 20th century—a lineage that extends back to Fritz Lang’s classic Metropolis. These wired aesthetic pleasures and pains dramatize Baudrillard’s “ecstasy of communication” and the provocation to “change nature if it is unjust” of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. Today, radical propositions for collectivizing the labor of reproduction through the technological are explored in the meta-political project of Xenofeminism by Laboria Cuboniks, the left offshoot of Transhumanism. Giger’s use of the airbrush and found mechanical levers, switches, cables and inputs situates his artistic production within the evolution of technological affordance. His cast of an altered IBM microchip to adorn Debbie Harry is a premonition of the ways in which woven circuits of computation would become the dominant vectors for identity and expression.

Again, La Cava:

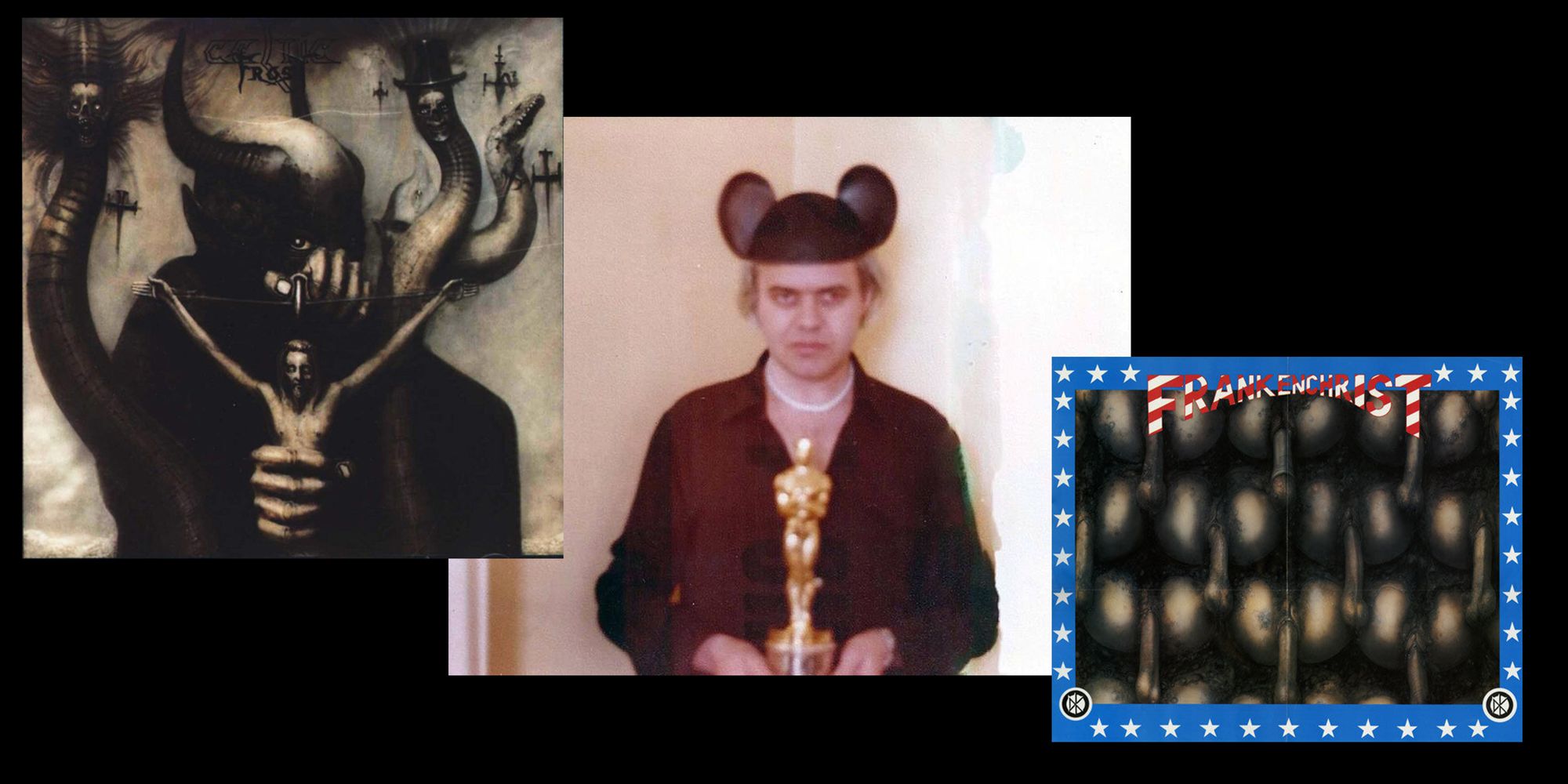

“There’s a photograph of artist H.R. Giger holding his 1980 Oscar for Visual Effects (Alien, 1979) while wearing souvenir Mickey Mouse ears that he got at nearby Disneyland before the awards ceremony. Refusing to take the hat off, Giger stares ahead with dark, stubborn eyes wearing a white choker band, and a black button-down shirt, while holding the new Oscar at his chest. In silhouette he’s something like a symmetrical monster with big round ears; bionic hood ornament. The son of a Swiss chemist, Giger had gone Hollywood.”

This self-awareness of the power of one’s imagery—of its ability to engage in the production and dispersal of aesthetic viruses—constitutes both a challenge and a threat to the centralized models of power that systems like Hollywood both generate and operate within. James Cameron acknowledges as much in his letter to Giger addressing his dismissal from the Alien sequel:

"Mr. Giger's visual stamp was so powerful and pervasive in 'Alien' (a major contributor to its success, I believe) that I felt the risk of being overwhelmed by him and his world, if we had brought him into a production where in a sense, he had more reason to be there than I did.”

Although pushed out of the Alien saga, his vision lived on through subsequent reproductions of his sculptures.

This pattern is a repeated motif throughout Giger’s career: commissioned spec work is forestalled, but then finds new life in divergent and sometimes unexpected ways. The HRGNYC exhibition includes a Giger proposal for SWATCH: an S&M bust with wristwatches for straps that never went into production. For the production bible for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s now-legendary attempt to make a cinematic version of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic Dune, Giger contributed the visual identity for the evil House Harkonnen. Although Jodorowsky’s version never succeeded in acquiring the necessary financing to make the film, Giger’s imagery had entered into visual culture, where it spread like a kind of infection. Giger’s work on Alien was a direct result of Giger having met young filmmaker and screenwriter Dan O’Bannon on the Dune project; when Alien was in pre-production, O’Bannon recommended Giger to Ridley Scott. Alien introduced the Xenomorph to the world, and the look of cinematic science fiction would never be the same. From there, Giger’s vision made its way into unlikely places: a Pioneer advert made use of his Castle design, while the Harkonnen throne held space for New York’s subculture club scene in the legendary Limelight’s VIP Giger Room. Lomex curator Alexander Shulan spoke with club owner Peter Gatien about the aura of Giger’s work in this setting for Interview Magazine:

“Giger was renowned, especially from Alien. It was sort of haunting, but just being in a church is a little bit haunting. The cast aluminum work that he did was museum quality. It was unique and it was fun—and fun is what you’re selling in a nightclub. People loved it.”

Gatien goes on to speculate about the indirect effect of Giger’s work along another vector:

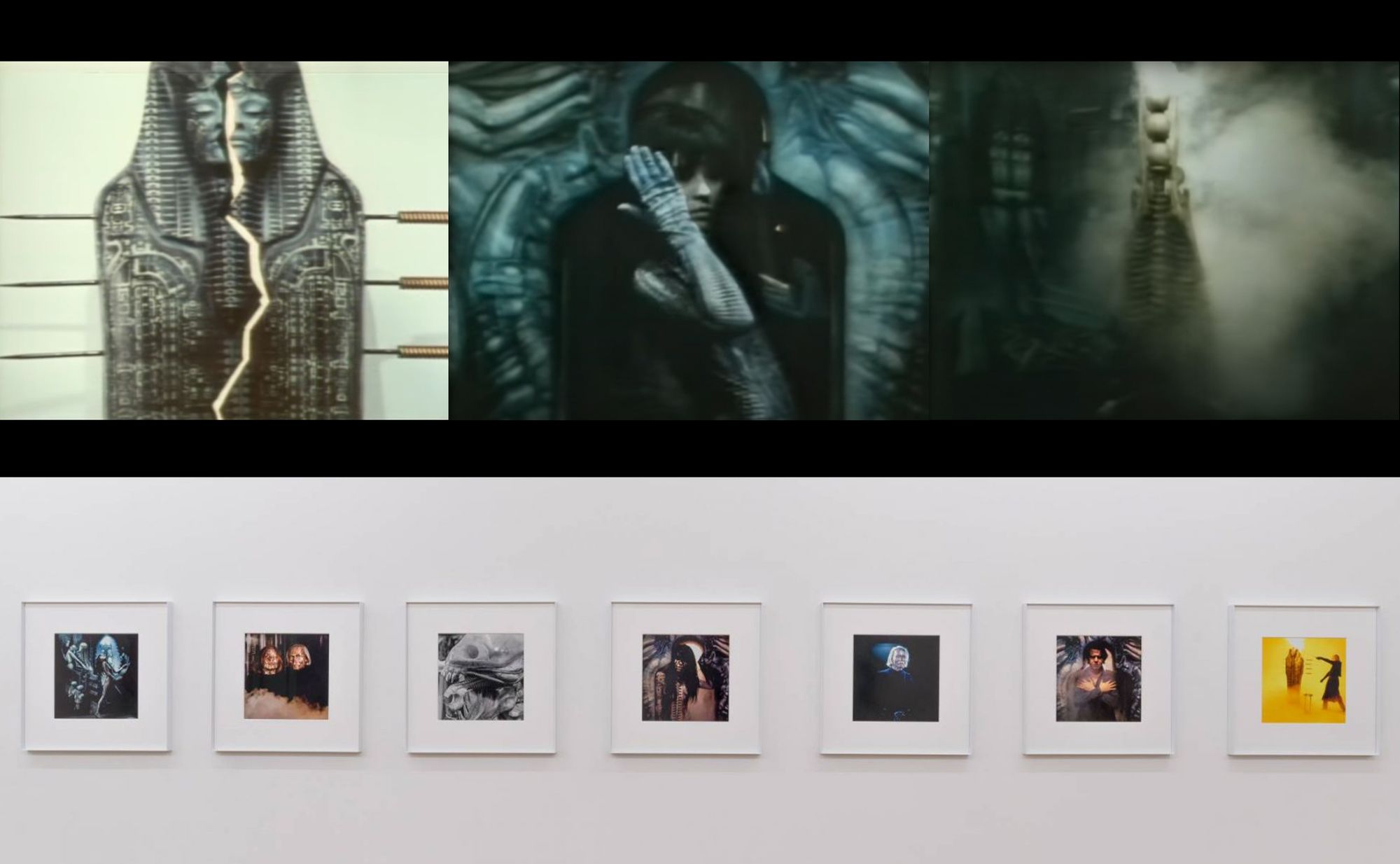

“I also think nightlife was inspiring to a lot of artists, especially clothing designers. I remember Jean Paul Gaultier and Thierry Mugler sitting at Limelight, or Tunnel or wherever, and then the next spring you’d see the looks [from the club] on the runway. A lot of their fashions followed the street: the kids, the people coming in. Obviously they had better fabrics and better accessories and that kind of stuff. But a lot of the inspiration came from New York nightlife. I was always very happy that we were part of it.”

This movement of an artist’s sensibility along two parallel tracks of dispersion—through mainstream blockbusters on the one hand and underground cult scenes on the other— illustrates the way in which capital works to curtail divergence, coopting radical visions in order to transform them into controllable/profitable elements, only to inadvertently generate even more radical strangeness when the alienated returns in unpredictable ways. The aesthetic flow between commercial success of L.A. and underground punk NYC is described by La Cava,

“Unlike Los Angeles freeways, there are underground subways and cooling systems. Stein explains it as the artist’s insistence on the city as inverted crucifix.

Everything happens below the skyscraper; horizontal action hidden in tall vertical structures. This recalls Giger’s album cover for Celtic Frost’s To Mega Therion (1985), where Christ is object: the slingshot in the hands of a demon. That same year, Dead Kennedys frontman Jello Biafra would try to use Giger’s painting known as Landscape XX or Penis Landscape (a pattern of penises entering vulvas) for the album cover of Frankenchrist (1985). it became a pull-out poster instead, but even as an insert, the work would stir up censorship controversy, a foil to Giger’s Mickey Mouse-eared gaze."

With the development of the internet, the vectors for aesthetic dispersal have undergone tectonic shifts and expansions. One effect of this is that subcultures with previously limited half-lives of influence have been able to persist, sometimes flywheeling into massively distributed scenes without ever needing to make themselves known to the mainstream. Giger’s dark but seductive vision informed the visual sensibilities of millions of young artists sharing their work on the website Deviant Art—while the artworld proper has struggled to deal with steadily weakening cultural authority in a digitally-mediated and aesthetically-flattened landscape. We now find ourselves at a crossroads between the coming virtualization of culture and the fleeting legacy of undocumented hidden subcultures. Perhaps we can learn a strategy for persistence from Giger’s compressed terrors: make work that unfolds over time as future fans observe from a more technologically mediated vantage point. In 2022, Giger’s corpus appears at once anticipatory and timely, a machine-age gothic romanticism that had continually respawned itself in the face of neoliberalism’s techno-positivity: new wave revival (Molchat Doma), nightcore, and the algorithmic egregore of hyperpop. Welcome to the “post-cringe” moment.

The faux tension between popular Hollywood spectacle and the velvet-roped-off fine art world demands to be transgressed by the surrealist. In this tendency is a desire to inject the heightened state of emotion that fantasy produces into the superstructure of culture. Giger’s travels through Hollywood sowed the seeds of what would morph into an entire movement of sci-fi fantasy. The populism of a subculture is such that through movies, books and comics millions of outsiders found escape in imagined virtual worlds. Crucially, this collective imaginary arrived before media technology could actualize these relations. Giger’s world front-ran the development of the virtual spaces we live in today. It is this dynamic (of fantasy inspiring technologist and theorist) that is responsible for the durability of his images. His work feels just as current today because we are only just now starting manifest the true ecstatic terror of its implications: the fusion of human and machine into the post-human. Now, as we are forced daily to come to terms with the digitalization of life, Giger’s work emerges once again in popular culture—this time, perhaps, to be latently canonized for its prophetic qualities.

As we move towards “The Metaverse” titans of digital industry attempt to colonize this new frontier with friendly boardrooms and classrooms filled with torso-up avatars gliding about and presenting pitch decks. The virtual horizon is a contested space. Giger’s work offers a contrasting seductive vision of uninhibited release and utter terror. His idea of the virtual is a more elucidating portrayal of a Lacanian unconscious death drive than the corporate sterility offered by Zuckerburg. It is no wonder then that a favorite digital skin of VR Chat users is the Xenomorph. An asexually reproducing alien driven by desires beyond comprehension is a more accurate reflection of the creatures we create through these new medias. Giger's interwoven beings linked by brainstems and embedded in cybernetic networks are accurate depictions of the architecture of techno-capital.

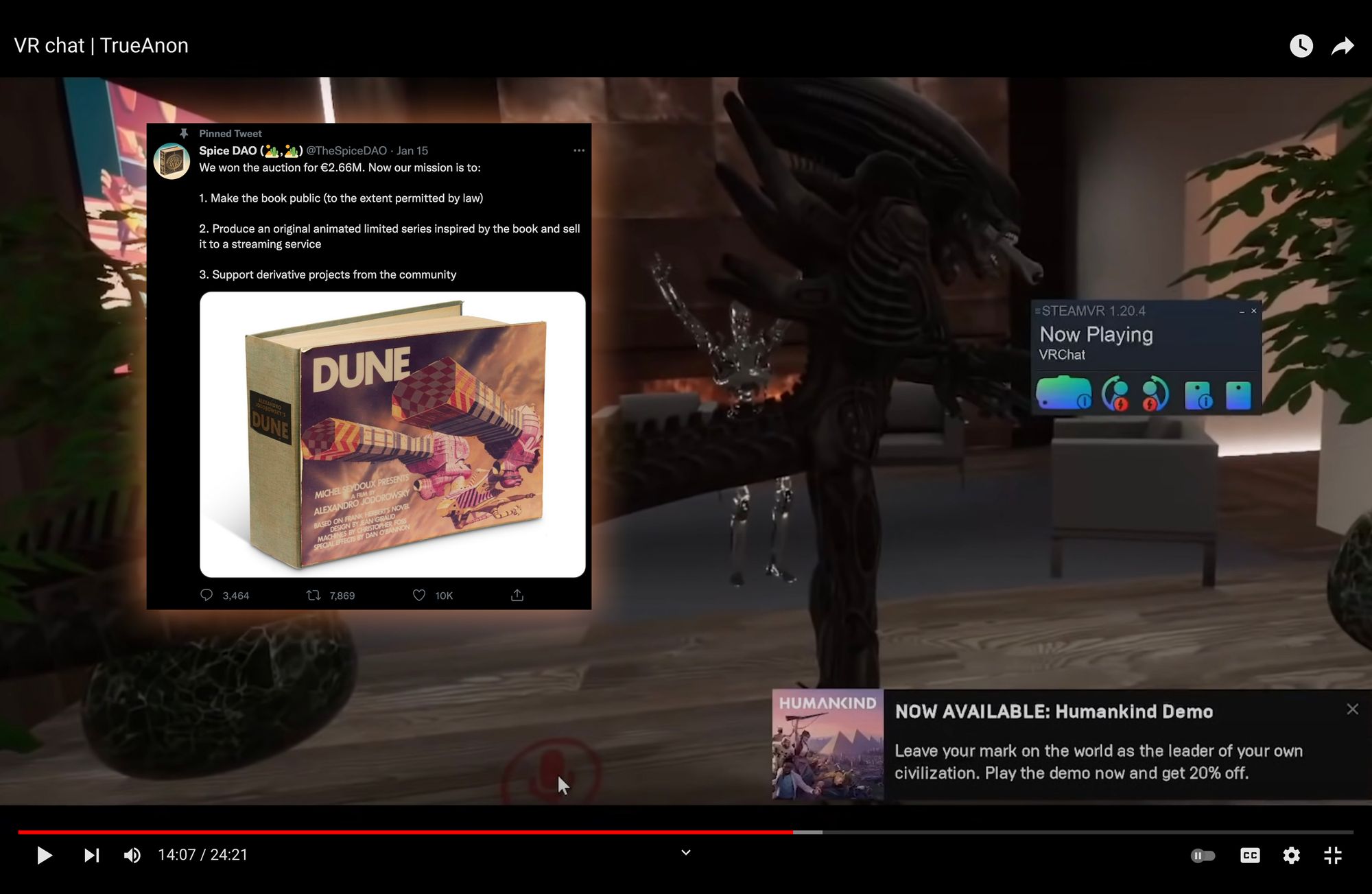

Since the beginning of the public internet, corporate design teams have attempted to visualize cyberspace through user interface design, unassuming cartoon avatars and slick graphics. While making the online accessible, these attempts also obfuscate the mechanism of digital power. Cyberspace is not a place we go to, it is the hyper-connections between users that constitutes the virtual. We have become painfully/pleasure-fully interconnected by addictive chemical processes to systems beyond comprehension: we are now pseudo-discreet entities lit by the phosphorescent glow of Giger’s tableau. This biomechanical fusion produces strange hiveminds, like “SpaceDAO” paying almost three million dollars for a rare copy of Jodoworsky’s Dune. Rather than resisting this shift or turning back towards reactionary physicality, we should descend headfirst into this new digitalized nightmare, by doing so we can perhaps challenge the binary of digital capital, pushing through into realized fantasies of post-capitalist desire, devirtualizing new identities and forms radical collectivity in the process.

Jak Ritger is an independent artist based in Allston, MA. His recent project, COLLIDER, deals with architecture, deep history and artificial intelligence. This piece was edited by artist, Anthony Discenza who provided context on Giger's Dune to Alien career path. For more on Xenofeminism read Helen Hestor's book of the same name. KooKoo 1981 is out now via Kaleidoscope.